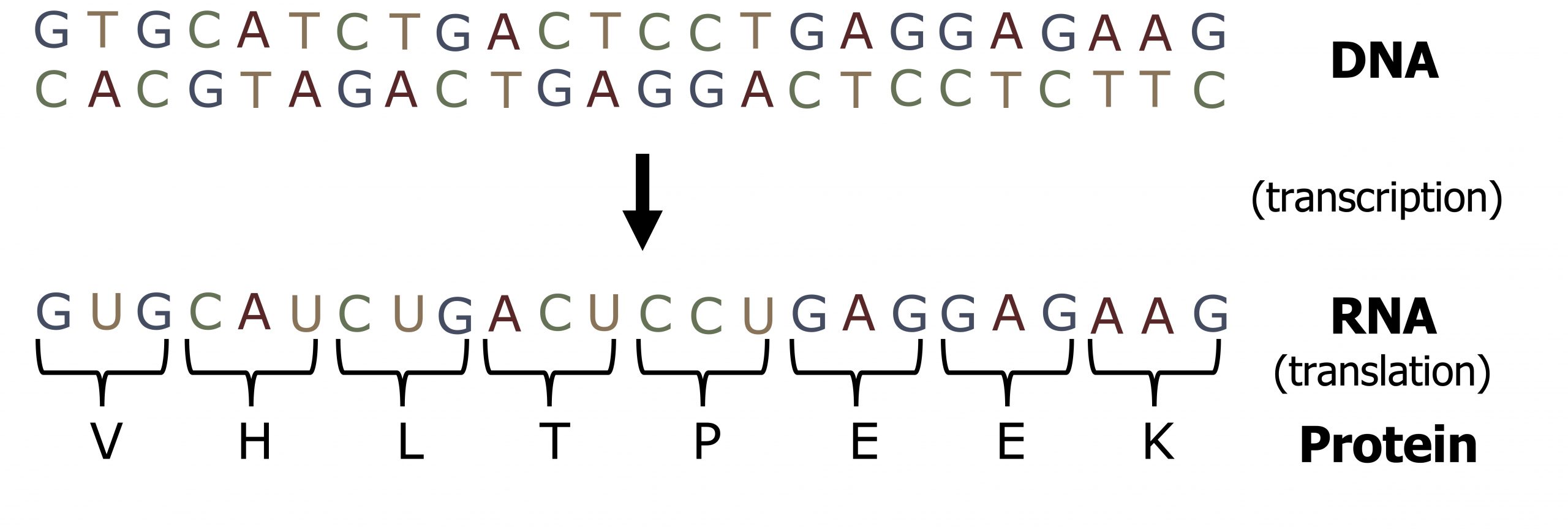

The flow of genetic information in cells from DNA to mRNA to protein is described by the central dogma, which states that genes specify the sequence of mRNAs, which in turn specify the sequence of amino acids making up all proteins. The decoding of one molecule to another is performed by specific proteins and RNAs. Because the information stored in DNA is so central to cellular function, it makes intuitive sense that the cell would make mRNA copies of this information for protein synthesis, while keeping the DNA itself intact and protected. The copying of DNA to RNA is relatively straightforward, with one nucleotide being added to the mRNA strand for every nucleotide read in the DNA strand.

The translation to protein is a bit more complex because three mRNA nucleotides correspond to one amino acid in the polypeptide sequence. However, the translation to protein is still systematic and colinear.

Unlike DNA synthesis, which only occurs during the S phase of the cell cycle, transcription and translation are continuous processes within the cell. The 5ʼ to 3ʼ strand of a DNA sequence functions as the coding ( nontemplate ) strand for the process of transcription such that the transcribed product will be identical to the coding strand, except for the insertion of uracil for thymidine (figure 11.1). The transcribed mRNA will serve as the template for protein translation.

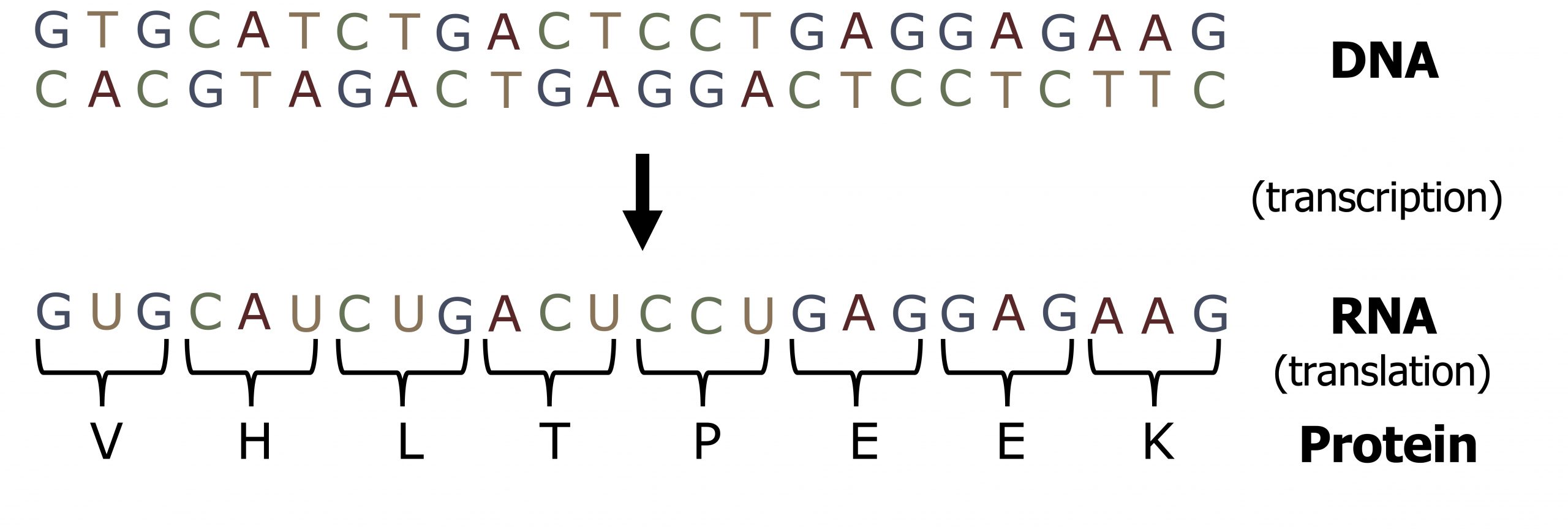

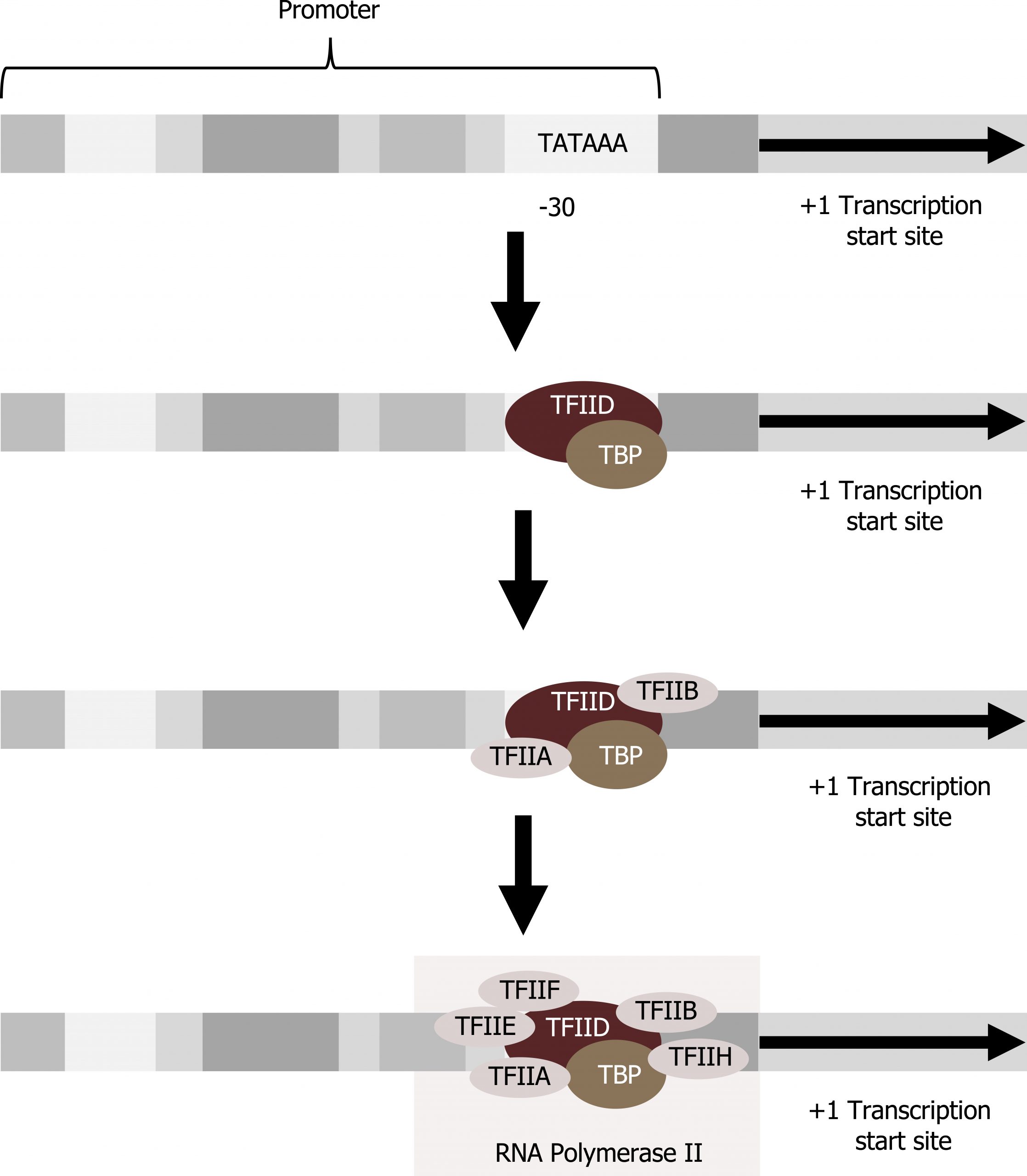

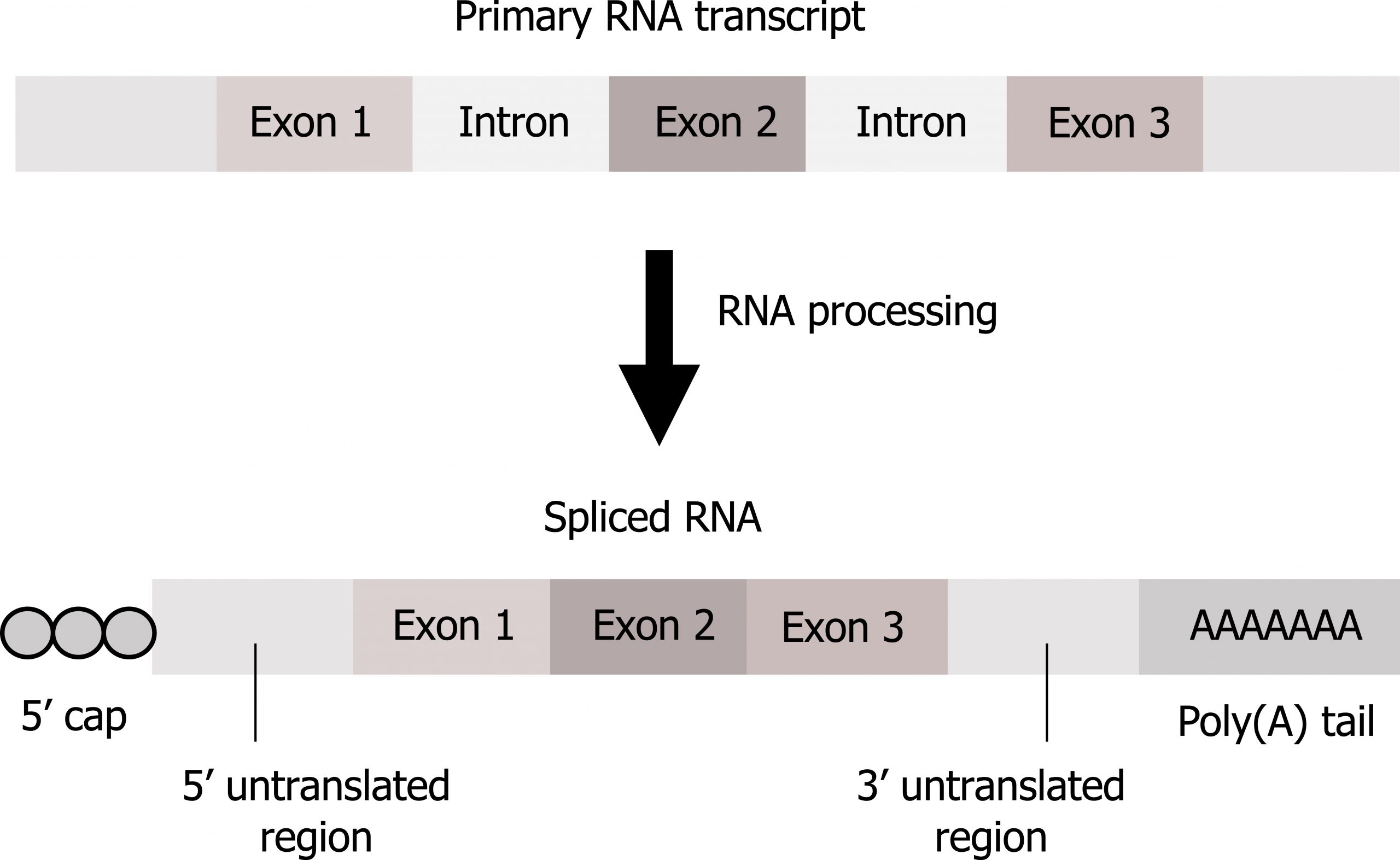

The chromosome is organized into functional units call genes. These are specific locations on a chromosome that are composed of a transcribed region and a regulatory (or promoter) region. The transcribed region is typically (but not always) downstream of the transcriptional start and contains the following DNA elements: a 5ʼ cap site (required for maturation of mRNA), translational start (AUG), introns and exons, and the polyadenylation site (figure 11.2).

The regulatory or promoter region is upstream of the transcriptional start and contains regulatory elements such as:

In eukaryotes, a single gene will produce one gene product as all genes are regulated independently. This is in contrast to prokaryotes, which regulate genes in an operon structure where one mRNA may be polycistronic and encode for multiple protein products.

RNA polymerase I is located in the nucleolus, a specialized nuclear substructure in which ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is transcribed, processed, and assembled into ribosomes. RNA polymerase I synthesizes all the rRNAs from the tandemly duplicated set of 18S , 5.8S, and 28S ribosomal genes. (Note that the “S” designation applies to “Svedberg” units, a nonadditive value that characterizes the speed at which a particle sediments during centrifugation.)

RNA polymerase II is located in the nucleus and synthesizes all protein-coding nuclear pre-mRNAs. Eukaryotic pre-mRNAs undergo extensive processing after transcription but before translation.

RNA polymerase II is responsible for transcribing the overwhelming majority of eukaryotic genes. RNA polymerase III is also located in the nucleus. This polymerase transcribes a variety of structural RNAs that includes the 5S pre-rRNA, transfer pre-RNAs (pre-tRNAs), and small nuclear pre-RNAs. The tRNAs have a critical role in translation; they serve as the “adaptor molecules” between the mRNA template and the growing polypeptide chain. Small nuclear RNAs have a variety of functions, including “splicing” pre-mRNAs and regulating transcription factors.

| RNA polymerase | Cellular compartment | Product of transcription | α-Amanitin sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Nucleolus | All rRNAs except 5S rRNA | Insensitive |

| II | Nucleus | All protein-coding nuclear pre-mRNAs | Extremely sensitive |

| III | Nucleus | 5S rRNA, tRNAs, and small nuclear RNAs | Moderately sensitive |

Table 11.1: Locations, products, and sensitivities of the three eukaryotic RNA polymerases.

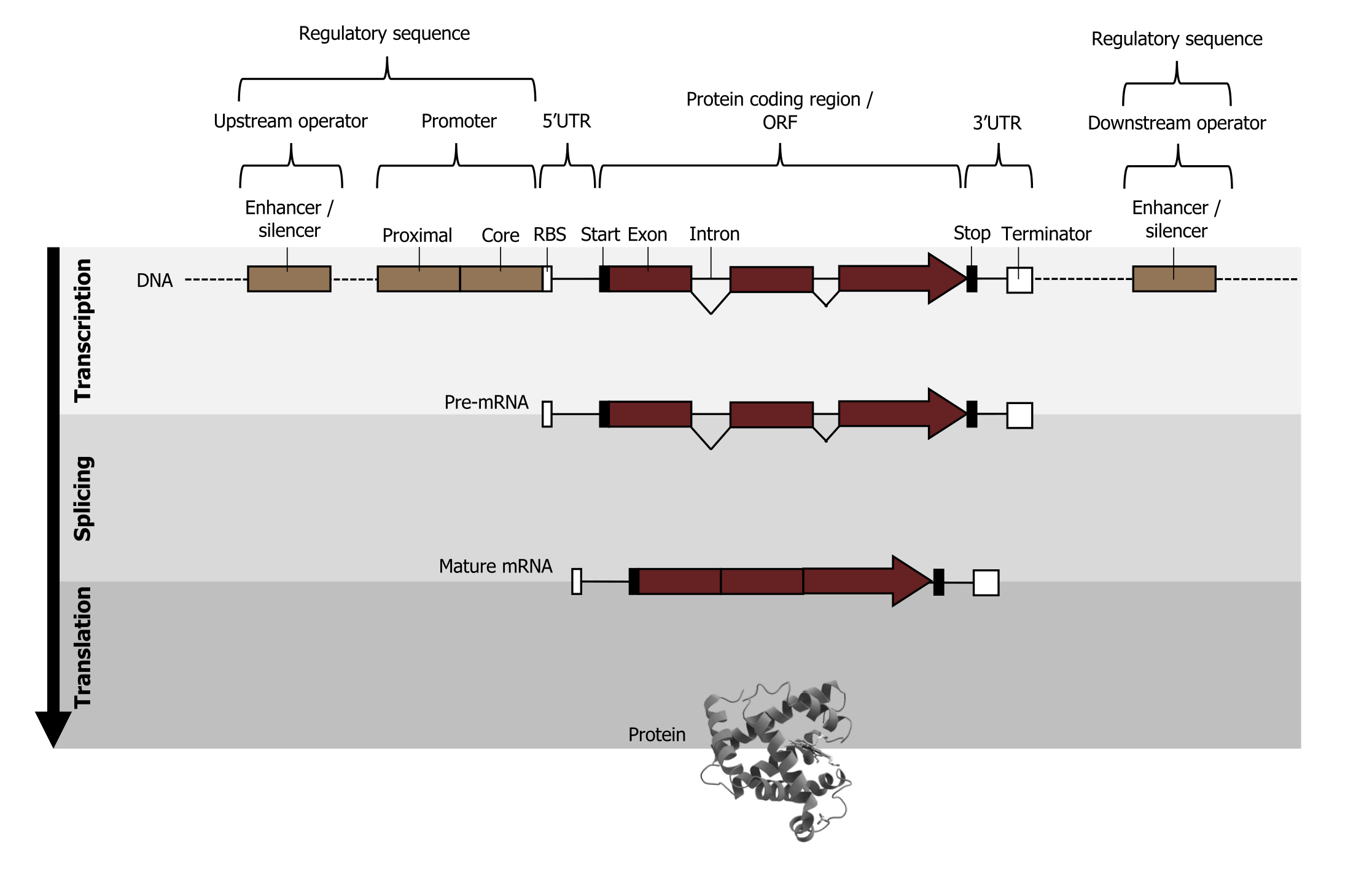

Eukaryotes assemble a complex of transcription factors required to recruit RNA polymerase II to a protein coding gene.

Transcription factors that bind to the promoter are called basal transcription factors. These basal factors are all called TFII (for transcription factor/polymerase II) plus an additional letter (A–J). The core complex is TFIID, which includes a TATA-binding protein (TBP). The other transcription factors systematically fall into place on the DNA template, with each one further stabilizing the pre-initiation complex and contributing to the recruitment of RNA polymerase II (figure 11.3).

Some eukaryotic promoters also have a conserved CAAT box (GGCCAATCT) at approximately -80. Further upstream of the TATA box, eukaryotic promoters may also contain one or more GC-rich boxes (GGCG) or octamer boxes (ATTTGCAT). These elements bind cellular factors that increase the efficiency of transcription initiation and are often identified in more “active” genes that are constantly being expressed by the cell. Other regulatory elements within the promoter region will be discussed in section 12.1.

Following the formation of the pre-initiation complex, the polymerase is released from the other transcription factors, and elongation is allowed to proceed with the polymerase synthesizing pre-mRNA in the 5′ to 3′ direction.

The termination of transcription is different for the different polymerases. Unlike in prokaryotes, elongation by RNA polymerase II in eukaryotes takes place 1,000 to 2,000 nucleotides beyond the end of the gene being transcribed. This pre-mRNA tail is subsequently removed by cleavage during mRNA processing. Alternatively, RNA polymerases I and III require termination signals. Genes transcribed by RNA polymerase I contain a specific eighteen-nucleotide sequence that is recognized by a termination protein. The process of termination in RNA polymerase III involves an mRNA hairpin similar to rho-independent termination of transcription in prokaryotes.

RNA is found in three different forms in the cell, and each is used for specific aspects of translation. Not all RNA that is transcribed is translated into a protein product; some transcribed RNA (rRNA and tRNA) is fully functional in the RNA form. mRNA (messenger RNA) is transcribed by RNA pol II.

In eukaryotes, pre-mRNA requires maturation before use in translation including (figure 11.4):

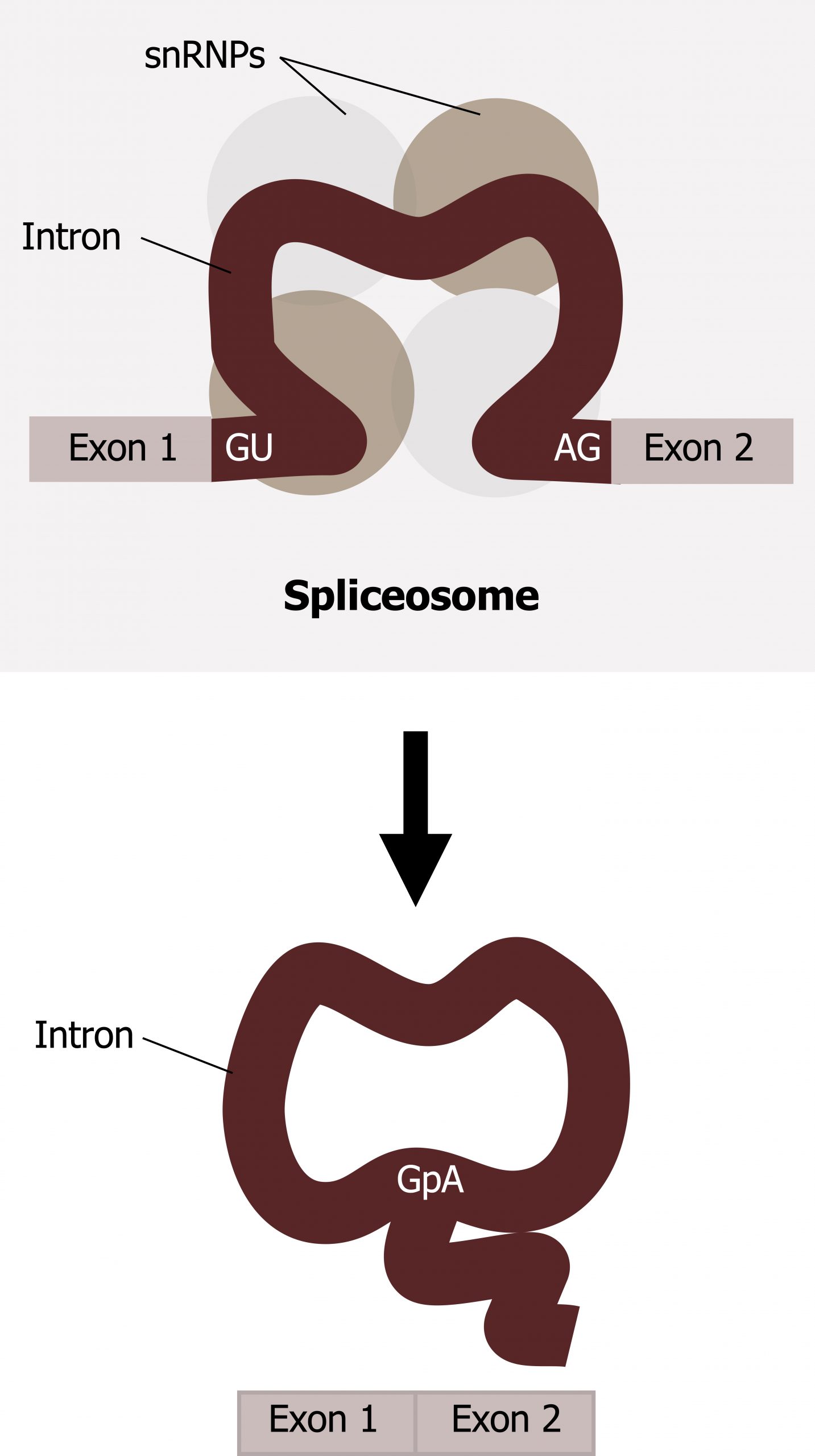

Splicing is a complex process mediated by a large protein RNA-associated complex called the spliceosome. The structure contains both proteins and small nuclear (sn)RNA. (Note antibodies to snRNAs are specific for systemic lupus.) Intronic sequences usually have GU at their 5′ end and AG at their 3′ end. An adenosine (A) is typically found at the branching point within the intron sequence. Small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) of the spliceosome recognize intron‒exon junctions and splice out the intron as a “lariat” structure. Splicing starts with an autocatalytic cleavage of the 5ʼ end of the intron leading to the formation of a circular or lariat where a 5′ UG sequence pairs with an internal adenine (A) or branch site. Finally the 3ʼ end of the intron is cleaved, and the intron is released as a lariat, and the right side of the exon is spliced to the left side. Alternative splicing of introns and exons generates protein variation from a single mRNA (figure 11.5).

tRNA, transfer RNA, is transcribed by RNA pol III, and like mRNA it requires maturation including:

tRNAs also are typical of base modifications generating nonconventional bases allowing base-pairing to several codons. This duplicity of binding is usually due to wobble in the third base pair. tRNA primarily functions to bring amino acids to the ribosome during protein translation. The anticodon on tRNA pairs with the codon on mRNA, and this determines which amino acid is added to the growing polypeptide chain.

rRNA, ribosomal RNA, is transcribed by RNA poly I and III and requires maturation that is slightly different from mRNA and tRNA. This RNA product is not translated but rather requires methylation and is incorporated into the protein as structural support. The 18S RNA is incorporated into the 40S ribosomal subunit, and the 28S, 5.8S, and 5S is incorporated into the 60S ribosomal subunit. These combine to make the full 80S ribosome required for protein translation.

Text

Clark, M. A. Biology, 2nd ed. Houston, TX: OpenStax College, Rice University, 2018, Chapter 15: Genes and Proteins.

Karp, G., and J. G. Patton. Cell and Molecular Biology: Concepts and Experiments, 7th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2013, Chapter 11: Gene Expression: From Transcription to Translation.

Le, T., and V. Bhushan. First Aid for the USMLE Step 1, 29th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Education, 2018, 39, 41–45.

Nussbaum, R. L., R. R. McInnes, H. F. Willard, A. Hamosh, and M. W. Thompson. Thompson & Thompson Genetics in Medicine, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier, 2016, Chapter 3: The Human Genome: Gene Structure and Function.

Figures

Grey, Kindred, Figure 11.4 Overview of mRNA processing involving the removal of introns (splicing), addition of a 5’ cap and 3’ tail. 2021. https://archive.org/details/11.4_20210926. CC BY 4.0.

Lieberman M, Peet A. Figure 11.1 Co-linearity of DNA and RNA. Adapted under Fair Use from Marks’ Basic Medical Biochemistry. 5th Ed. pp 277. Figure 15.3 Reading frame of messenger RNA (mRNA). 2017.

Lieberman M, Peet A. Figure 11.2 Schematic view of a eukaryotic gene structure. Adapted under Fair Use from Marks’ Basic Medical Biochemistry. 5th Ed. pp 255. Figure 14.4 A schematic view of a eukarytoic gene, and steps required to produce a protein product. 2017. Added Myoglobin by AzaToth. Public domain. From Wikimedia Commons.

Translation is the process by which mRNAs are converted into protein products through the interactions of mRNA, tRNA, and rRNA. Even before an mRNA is translated, a cell must invest energy to build each of its ribosomes, a complex macromolecule composed of structural and catalytic rRNAs, and many distinct polypeptides. In eukaryotes, the nucleolus is completely specialized for the synthesis and assembly of rRNAs.

Ribosomes exist in the cytoplasm and rough endoplasmic reticulum of eukaryotes. Ribosomes dissociate into large and small subunits when they are not synthesizing proteins and reassociate during the initiation of translation.

Each mRNA molecule is simultaneously translated by many ribosomes, all synthesizing protein in the same direction: reading the mRNA from 5′ to 3′ and synthesizing the polypeptide from the N terminus to the C terminus. The complete mRNA/poly-ribosome structure is called a polysome.

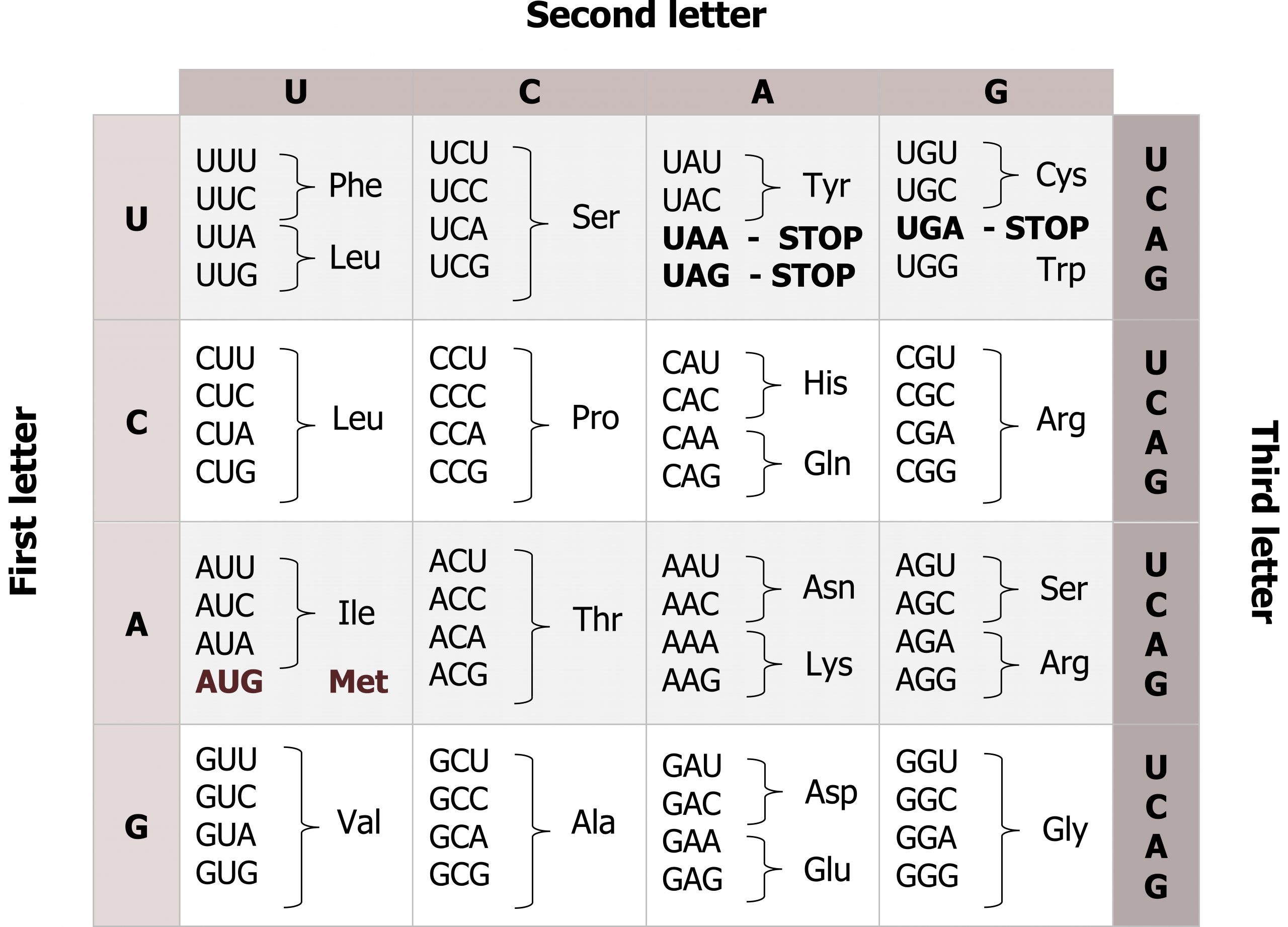

mRNAs are read three base pairs at a time (codon), and the reading frame will start with the first AUG (figures 11.6 and 11.7). Translation requires the formation of an aminoacyl-tRNA where tRNA is charged with the correct amino acid and brought to the translational machinery. Through the process of tRNA “charging,” each tRNA molecule is linked to its correct amino acid by one of a group of enzymes called aminoacyl tRNA synthetases.

At least one type of aminoacyl tRNA synthetase exists for each of the twenty amino acids; the exact number of aminoacyl tRNA synthetases varies by species. These enzymes first bind and hydrolyze ATP to catalyze a high-energy bond between an amino acid and adenosine monophosphate (AMP). The activated amino acid is then transferred to the tRNA, and AMP is released. The term “charging” is appropriate, since the high-energy bond that attaches an amino acid to its tRNA is later used to drive the formation of the peptide bond. Each tRNA is named for its amino acid.

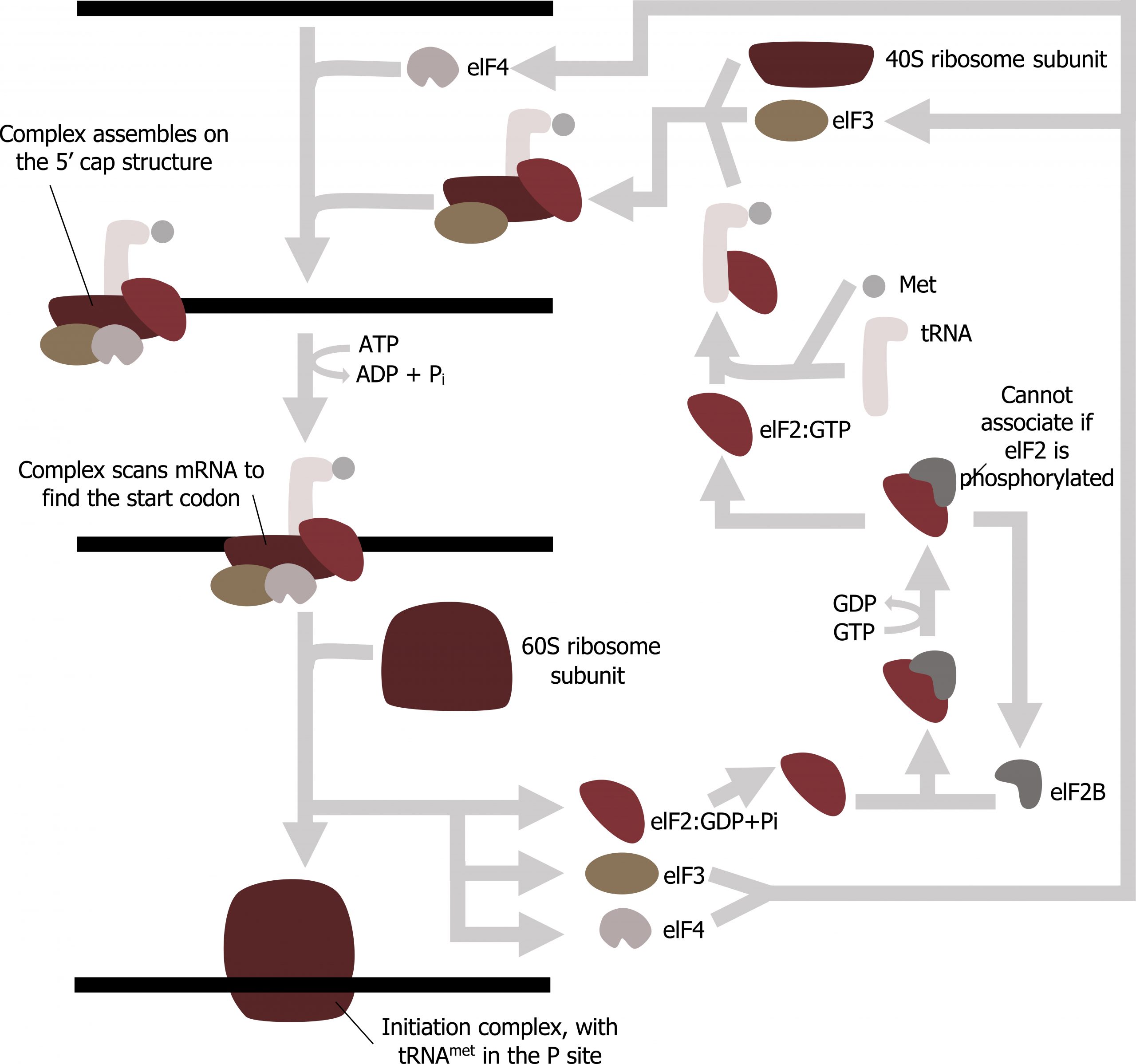

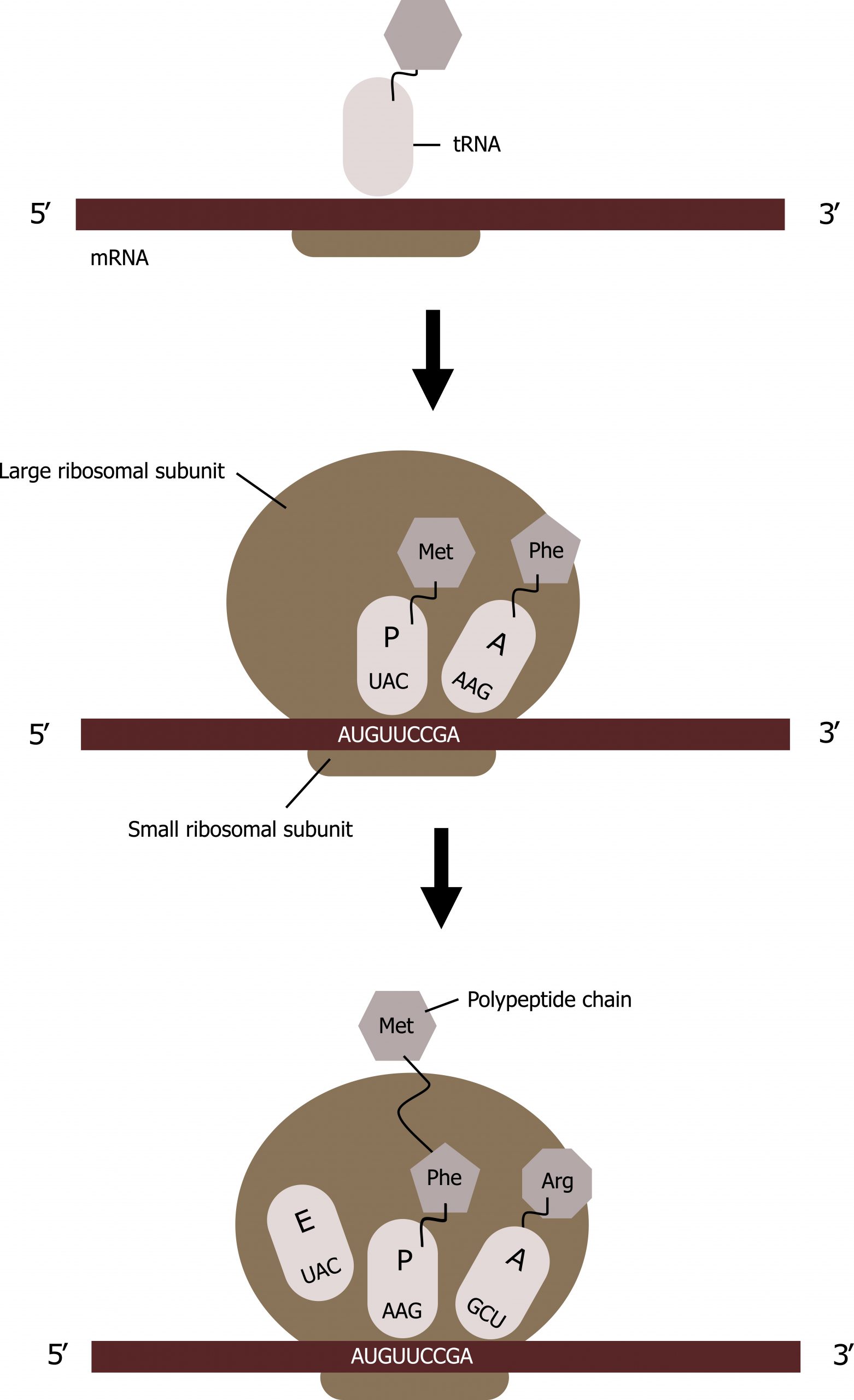

Translation is initiated by the assembly of the small ribosomal subunit ( 40S ) with initiation factors (IF), which recognize the 5ʼ cap of the mRNA. This is referred to as the cap-binding complex, and this will scan the mRNA for the initial AUG needed to start translation. Once at the cap, the initiation complex tracks along the mRNA in the 5′ to 3′ direction, searching for the AUG start codon. Many eukaryotic mRNAs are translated from the first AUG, but this is not always the case. Once the appropriate AUG is identified, the other proteins and CBP dissociate, and the 60S subunit binds to the complex of Met- tRNAi , mRNA, and the 40S subunit. This step completes the initiation of translation in eukaryotes (figure 11.8).

The ribosome has three locations for tRNA binding: A, P, and E sites.

Translation elongation requires energy in the form of GTP, and additional elongation factors (EFs) are required for this process. Elongation proceeds with charged tRNAs sequentially entering and leaving the ribosome as each new amino acid is added to the polypeptide chain. Movement of a tRNA from A to P to E sites is induced by conformational changes that advance the ribosome by three bases in the 3′ direction. GTP energy is required both for the binding of a new aminoacyl-tRNA to the A site and for its translocation to the P site after formation of the peptide bond.

Peptide bonds form between the amino group of the amino acid attached to the A-site tRNA and the carboxyl group of the amino acid attached to the P-site tRNA. A new tRNA with the corresponding amino acid coded for by the mRNA will enter into the A site of the ribosome.

The amino acid attached to the tRNA in the P site will be transferred to the tRNA in the A site; this is referred to as the peptidyl transferase react ion. The tRNAs will slide such that the tRNA in the P site will move to the E site and the tRNA in the A site will move to the P site. The tRNA in the E site will be released, and a new tRNA will enter into the A site, and the process will continue with the addition of tRNAs in the manner until the full message is transcribed (figure 11.8).

Termination of translation occurs when a nonsense codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA) is encountered. Upon aligning with the A site, these nonsense codons are recognized by protein release factors that resemble tRNAs.

The release factors in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes instruct peptidyl transferase to add a water molecule to the carboxyl end of the P-site amino acid. This reaction forces the P-site amino acid to detach from its tRNA, and the newly made protein is released.

The small and large ribosomal subunits dissociate from the mRNA and from each other; they are recruited almost immediately into another translation initiation complex. After many ribosomes have completed translation, the mRNA is degraded so the nucleotides can be reused in another transcription reaction.

Text

Clark, M. A. Biology, 2nd ed. Houston, TX: OpenStax College, Rice University, 2018, Chapter 15: Genes and Proteins.

Karp, G., and J. G. Patton. Cell and Molecular Biology: Concepts and Experiments, 7th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2013, Chapter 11: Gene Expression: From Transcription to Translation.

Le, T., and V. Bhushan. First Aid for the USMLE Step 1, 29th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Education, 2018, 39, 41–45.

Nussbaum, R. L., R. R. McInnes, H. F. Willard, A. Hamosh, and M. W. Thompson. Thompson & Thompson Genetics in Medicine, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier, 2016, Chapter 3: The Human Genome: Gene Structure and Function.

Figures

Grey, Kindred, Figure 11.6 Genetic code, each codons is 3 nucleotides corresponding to a specific amino acid. The code is degenerate meaning several codes are present for the same amino acid and the codes for similar amino acids are clustered. 2021. https://archive.org/details/11.6_20210926. CC BY 4.0.

Grey, Kindred, Figure 11.7: Summary of translational initiation. 2021. CC BY SA 3.0. Adapted from Eukaryotic Translation Initiation by Chewie. CC BY SA 3.0. From Wikimedia Commons.

Grey, Kindred, Figure 11.8 Summary of translational elongation. 2021. CC BY 4.0.